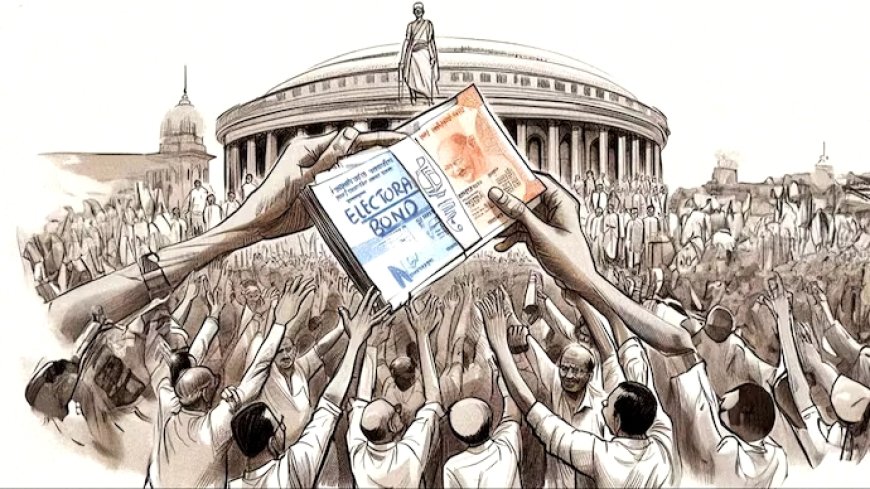

Electoral Bonds: Redefining Democracy

An electoral bond is like a promissory note. It is an instrument that is payable to the bearer upon demand. Unlike a promissory note, which contains the details of the payer and payee, an electoral bond has no information on the parties in the transaction, providing complete anonymity and confidentiality to the parties.

When presenting the 2017-18 Union Budget, Former Union Finance Minister Arun Jaitley stated that after 70 years of Independence, “the country has not been able to evolve a transparent method of funding political parties, which is vital to the system of free and fair elections.” He proposed the Electoral Bonds Scheme, designed to “cleanse the system” of political funding. Under the 2018 Scheme, certain State Bank of India (SBI) branches were authorised to sell electoral bonds. The SBI offers bonds in denominations of ₹1,000, ₹10,000, ₹1,00,000, ₹10,00,000, and ₹1,00,00,000.

They are to be sold for 10 days in January, April, July, and October each year. The purchaser's identity remains anonymous to everyone except the SBI, who must record the buyer’s KYC (Know Your Customer) details.

Political parties that secured more than one per cent of votes “in the last general election to the House of the People (Lok Sabha) or a Legislative Assembly” are eligible to accept donations through electoral bonds. However, the political parties must encash the bond within 15 days of receiving it. Once this time frame expires, the money is deposited into the Prime Minister's Relief Fund

On 25 March 2019, the ECI filed an affidavit opposing the Electoral Bond Scheme, citing concerns about its impact on transparency in political finance. They highlighted the risk of unchecked foreign funding influencing Indian policies due to the lack of disclosure requirements for political parties.

Responding to the ECI's concerns, the Union government defended the Electoral Bond Scheme (EBS) as a pioneering step towards electoral reforms aimed at curbing the unregulated flow of black money in political funding. They emphasised the role of the State Bank of India (SBI) in ensuring accountability through KYC verification.

The Supreme Court took up the challenge to the EBS, directing political parties to submit details of donations, donors, and bank account numbers to the ECI in a sealed cover. Despite refraining from imposing an immediate stay on the scheme, the court acknowledged the issues' weightiness.

Over the following years, petitioners continued to approach the court seeking a stay on the scheme, expressing concerns about its implications for corporate funding, black money circulation, and corruption. The court denied these requests and underscored the need for comprehensive arguments. The case eventually reached a five-judge Constitution Bench, which heard arguments over three days. Petitioners stressed the voters' right to information about political funding, while the Union defended the scheme's confidentiality provisions to protect donors' privacy.

On 15 February 2024, Chief Justice DY Chandrachud led a five-judge panel of the Indian Supreme Court, where the court unanimously struck down the electoral bonds scheme, as well as amendments to the Representation of People Act, Companies Act and Income Tax Act, as unconstitutional. They found it "violative of RTI (Right to Information)" and of voters’ right to information about political funding under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution. They also pointed out that it "would lead to quid pro quo arrangements" between corporations and politicians. The court also ordered an immediate halt to the sale of electoral bonds and directed the SBI to provide purchase details to the ECI for publication on its official website.

In essence, the Supreme Court's decision represents a pivotal moment in India's democratic journey, reaffirming the principles of transparency, accountability, and the public's right to know in the country's electoral processes.